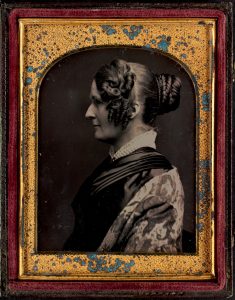

Female abolitionists played a key role in the abolitionist movement. In 1833, a group of Boston women decided to form their own organization. It was called the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, and it had both white and black members. The organization looked for ways to support the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society (a local branch of the American Anti-Slavery Society). In 1834, the female society organized the first of many Anti-Slavery Fairs to help raise money for the cause. Women from across Massachusetts donated quilts, articles of clothing, needlework, and other crafts for the fair. Letters written by Maria Weston Chapman, the fair’s organizer (pictured right), to other female abolitionists reveal how much work went into the fair’s planning. You can read these letters and others at the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts Project, a crowdsourcing platform where you can help transcribe abolitionist letters for future generations.

Female abolitionists played a key role in the abolitionist movement. In 1833, a group of Boston women decided to form their own organization. It was called the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, and it had both white and black members. The organization looked for ways to support the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society (a local branch of the American Anti-Slavery Society). In 1834, the female society organized the first of many Anti-Slavery Fairs to help raise money for the cause. Women from across Massachusetts donated quilts, articles of clothing, needlework, and other crafts for the fair. Letters written by Maria Weston Chapman, the fair’s organizer (pictured right), to other female abolitionists reveal how much work went into the fair’s planning. You can read these letters and others at the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts Project, a crowdsourcing platform where you can help transcribe abolitionist letters for future generations.

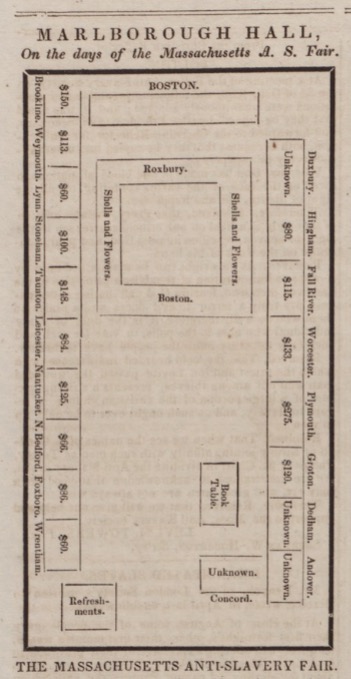

On November 8, 1839, The Liberator printed a floor plan of the 1839 Anti-Slavery Fair with booths hosted by sister societies from across Massachusetts. In the plan, you can see how much money each town’s society raised. Located in Marlborough Hall, the 1839 fair was open for four days and raised over $1,500, which was a large sum at the time. Marlborough Hall, which no longer exists today, originally stood in the heart of Boston, at Washington Street between Winter Street and Bromfield Street.

A sign above the entrance to the hall welcomed visitors. It read, “Freedom and Truth—By these We Conquer” in “letters a foot long,” according to an article written by Maria Weston Chapman for The Liberator. In the same article from November 1839, she described the fair at length:

“An interesting assemblage is gathered within:—the anti-slavery women of Massachusetts, from all parts of their beloved Commonwealth, superintending the sale of the various articles of taste, ingenuity and utility, which they have for months been busied in preparing for this occasion...Never was there a finer display of money’s worth, whether the purchaser be in search of the useful or the beautiful.”

Many months before the fair, women began sewing bonnets, lace, linen, and quilts to donate. One such quilt still survives today and can be viewed at Historic New England.

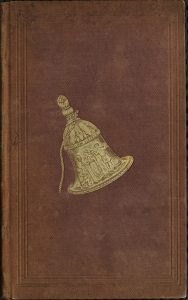

Maria Weston Chapman also edited an annual gift-book titled, The Liberty Bell, filled with poetry and short fiction.

Visitors could buy this gift-book as a souvenir of their visit to the fair. On the 1844 cover, there is a golden bell with three figures pictured on it. At center is a woman representing Liberty. She holds a staff with a “liberty cap” on top. In ancient Rome, freed slaves showed their freedom by wearing a soft felt cap. Known as the liberty cap, the symbol was used to represent the figure of Liberty and appeared often in abolitionist works.

To the left of Liberty, a chained slave pleads for freedom. On the right, a freed slave proudly breaks out of his chains. This hopeful picture showed the optimism and determination of the abolitionist movement at a time when it faced disapproval from both Southerners and Northerners. The money raised at the annual Anti-Slavery Fair allowed abolitionists to print anti-slavery publications. It also let them travel across America to speak to large crowds about the horrors of slavery. Because of these efforts, public opinion began to shift, and more and more Americans joined the abolitionist cause.

Kelsey Gustin, the author of this post, is a Humanities PhD intern at the Boston Public Library and a doctoral student at Boston University in the History of Art and Architecture. She specializes in nineteenth and twentieth-century American art and is presently writing her dissertation on representations of working-class immigrants in New York City from 1890 to 1920.

Kelsey Gustin, the author of this post, is a Humanities PhD intern at the Boston Public Library and a doctoral student at Boston University in the History of Art and Architecture. She specializes in nineteenth and twentieth-century American art and is presently writing her dissertation on representations of working-class immigrants in New York City from 1890 to 1920.

Add a comment to: The Anti-slavery Fair